|

| Courtesy: Penn State News Letter |

Going forward with the concept of ‘organs-on-chip’ that mimic the physiological conditions in-vivo, researchers at the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Engineering and Applied Science have developed ‘placenta-on-a-chip’ to look at the placental barrier and drug transport in pregnancy.

This is a real breakthrough to study the maternal-fetal drug transport across the placenta, as the placental barrier can never be exactly replicated in the lab and in-vivo studies in humans are not ethical. Pregnant women are not included as research subjects because of the risk of teratogenicity. Animal models are not exactly able to mimic human physiology.

We are all aware of the famous ‘Thalidomide’ disaster, in which a drug for morning sickness, crossed the placental barrier in humans and caused multiple birth defects, collectively known as ‘fetal thalidomide syndrome’ and deaths.

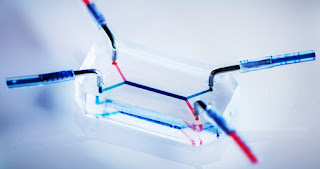

To address these issues, a team of researchers led by Dan Huh, Wilf Family Term Assistant Professor in Bioengineering at Penn and Cassidy Blundell, a graduate student in the Huh lab have developed a placenta-on-a-chip, using microfluidic channels in silicone casing.

The study was also published in the journal Advanced Healthcare Materials.

The two channels house human trophoblast cells on one side and endothelial cells on the other separated by a porous membrane. The unit mimics placental barrier and hence the permeability of the barrier to different drugs can be tested.

A blood-like fluid flows through the maternal side of the channel and the researchers can experiment by adding different drugs to the fluid and see the rate, amount of drug transferred to the fetal side of the channel.

“Ex vivo placental perfusion is a great method,” Huh said, “but it has a pretty high failure rate, and the experimental set-up is complicated: it’s prone to leaks and needs a high level of expertise. Most pharmaceutical companies are not going to be able to test their drugs using this method.”

Currently, to validate their model, the team has tested 2 drugs that they have already studied via ex vivo placental perfusion: heparin, an anticoagulant, and glyburide, used in the treatment of diabetes.

The placenta on the chip was able to simulate the drug transfer of these two drugs as it happens in human placenta and fetal interface. Heparin did not pass through the chip model as it is too large a molecule to breach the placental barrier and glyburide transfer was also limited as in real placenta to protect the fetus.

Huh further added, “We’re getting close, this study has given us confidence that the placenta-on-a-chip has tremendous potential as a screening platform to assess and predict drug transport in the human placenta.”

Besides its use by the pharmaceutical company to test various drugs, the ‘placenta-on-a-chip’ has tremendous potential in testing the transfer of supplements other than drugs like vitamins and nutritional supplement.