Combined oral contraceptive (COC) and anti-androgens (AA) are more effective than metformin for treating the symptoms of excess androgens and offer endometrial protection in adult women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) as compared to metformin alone. Addition of metformin to the treatment regimen improves glucose sensitivity and bring about weight loss report the results of a systematic review and metanalysis published in current issue of Journal of Human Reproduction Update.

PCOS is common endocrine disorder in women of the reproductive age and beyond. Most treatments are directed towards achieving conception in younger women who desire fertility but the treatment of women with PCOS who do not desire pregnancy is not standardized.

COC and anti-androgens with or without insulin sensitizers are commonly used. But, the efficacy and safety of these treatments in treating hyperandrogenemia and its effect on cardiometabolic risk factor are not well documented.

This review of RCTs was conducted to seek better therapeutic approach in this subset of women who do not desire fertility in terms of efficacy and safety.

The authors found 1522 articles abstract after going through PubMed and EMBASE until September 2017. After exclusion, 33 studies and 1521 women were included in the quantitative synthesis and in the meta-analyses. After statistical analysis, the outcomes were:

- COC and/or AA significantly improved the hirsutism score as compared to metformin alone.

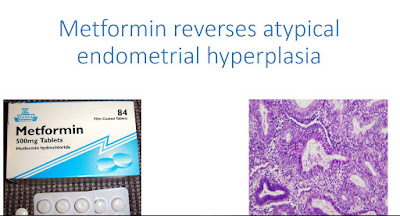

- COC and/or AA also was more effective in preventing endometrial hyperplasia as compared to metformin alone.

- COC was also found more effective in regularizing the menstrual cycle.

- Metformin helped in improving the cardiometabolic profile in these women because of its favorable effect on BMI.

- The use of COC and/or AA along with metformin did not affect the mean glucose levels but it did help bring down the fasting glucose levels.

- Both the therapies were comparable in terms of the effect on lipid profile, blood pressure or prevalence of hypertension, but the quality of evidence was low when these effects were explored.

The results of this systematic review and metanalysis provide scientific evidence to choose between treatment for adult women with PCOS based on symptoms and desired goal of therapy.